When, in the late 19th century, the chancellor Otto von Bismarck decided that the retirement age should be set at 65, a large proportionof workers at that time did not even reach that age. And those who did only survived an average of nine more years collecting their pension.

TEXT Javier Fernández ILLUSTRATION Getty Images y Thinkstock

Today, almost a century and a half later, 65 still remains the benchmark age for retirement we all have in mind, even though an increasing number of countries have had to progressively increase this reference point to 66, 67 or even more years of age. This is because that average of nine years – during which retired workers collected a pension in the year 1900 – has now risen to around 15 for most regions and countries, although there are cases, such as that of Spain, in which survival beyond 65 is fast approaching 20 years. In other words, what constitutes really good news, namely that people are living longer, has become a problem for countries, given that the aging population is putting a strain on what we know as the welfare state, particularly with regard to the payment of pensions.

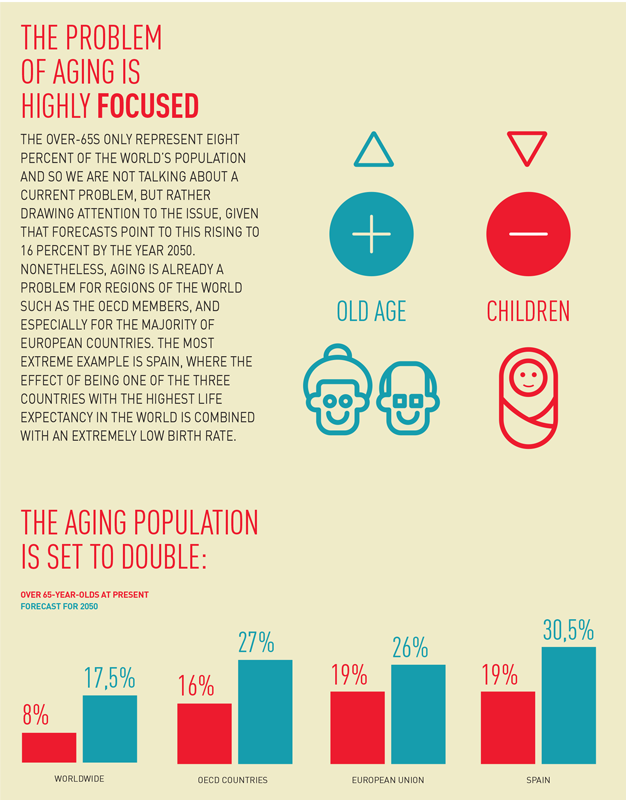

At this point, there can be no disputing the fact that aging has become a global problem and one that is increasing, given that life expectancy at birth increases each day by approximately six hours. But this is a problem whose effect is not the same across the board, as its impact is highly focused – as explained on page 10. Regardless of the starting position of each region of the world, the fact is that, by the year 2050, all countries will have twice as many people over the age of 65 as they have today, and this will lead to profound social changes for which they should start preparing.

Because most countries which have some sort of public pension system have built this on the basis of a distribution scheme, whereby active workers contribute a portion of their salary to pay the pensions of retirees who, in turn, did the same during their working lives. And this will also be the case in the future – as workers reach retirement age, it is hoped that the younger workers will be able to finance their pensions each month.

Why does this particularly affect pensions?

This scheme, based on intergenerational solidarity, has worked for many years without any major difficulties, until now when the aging population has changed the rules of the game. Pensioners are living ever longer and therefore easily use up the money they contributed throughout their working lives to the pensions of their elders. Moreover, because of demographic issues, ever fewer children are being born, i.e. there will be fewer future workers able to contribute to those pension payments. In addition, there has been a third effect: in some markets, the recent economic crisis has resulted in those responsible for contributing to the pension system earning a salary lower than the pensions collected by recently retired workers.

All countries, with greater or lesser speed, have started reacting to address this growing lack of financial sustainability within the system. In general, they have introduced reforms designed to increase future revenues for the system. These consist in creating funds that grow during phases of economic expansion to offset the deficits during the lean years, or taking action on the factors which determine the amount of the pension, basically three:

• Raise the retirement age: each year this is put back produces a twofold benefit – theoretically, workers continue contributing and, secondly, they will collect a pension for one year less of their lives.

• Calculate workers’ rights over more years, i.e. calculate what their pension should be according to what they have paid into the system over their working life, and not over a limited number of years, usually the last few. This leads to a reduction in the pension because, in the early years, wages are lower and, therefore, so are the contributions.

• Restrict pension rights through parametric reforms: require a greater number of years working and contributing in order to “start” being entitled to draw a pension; or else, rather than the inflation rate, other elements such as productivity, the development of the wages paying for its upkeep, or the financial “health” of the pension system itself should condition its future development.

Which solution has each country adopted?

Most have adopted all three, or a combination thereof. There is no set solution for tackling this problem. However, there is increasingly widespread agreement that the amount of the public pensions will tend to fall: there will always be public pensions because the states guarantee them, but they will not be sufficient. There is also consensus on the fact that no pure system – whether distribution or capitalization, such as the Chilean model – has the capacity to act alone any longer. For this reason, most countries are opting for the joint development of the two retirement planning models: distribution and capitalization.

The goal is simple to understand, yet difficult to implement. What must be done is to convince workers to save for their own retirement and not just rely on the pensions from the distribution system, as the public pensions are going to be increasingly limited. In most countries the replacement rate (percentage of a worker’s pre-retirement income received as a pension) already stands at 50 percent, at most. This is the trend, even for countries like Spain or Greece where the European Commission warns that the replacement rates will fall by over 30 percent in the coming years.

The British example

Each country has its own savings/retirement model to complement the public pensions but, in general, they are all compulsory or semi-compulsory, linked to the working life when workers have some saving capacity, and clearly based on incentive schemes: employees contribute and the employer and/or the state complement this saving.

No one model is better than another, nor do all suit all countries, but the British scheme, still in its implementation phase, is felt to be one that could be easily exported, obviously with certain national adaptations. By default all British workers are obliged to set aside a portion of their salary as savings for their own retirement. The employer adds another portion, while the state also encourages this saving scheme through tax incentives. When this model becomes universal throughout the labor market in 2018, each worker will be setting aside eight percent of their salary toward their future pension. Five percent will come from the worker, two percent from the employer, and one percent from the state through tax breaks. What is different about this new system is that workers do not have to opt in, but rather are automatically incorporated into the compulsory savings scheme, unless they expressly manifest their wish to opt out. Even so, the employer periodically incorporates them once again and they have to expressly opt out again if they do not wish to save for their retirement.

Pensions hit countries beneath the waterline

The emerging countries, which barely have an aging population issue and maintain high birth rates, do not have to raise this issue at all. But in the more developed countries of the OECD and, more specifically, Europe, dealing with the various different effects of aging cannot wait. This is because it hits the economy hard, not just in terms of expenditure (increased consumption of health and dependency resources), but also revenue, as dwindling pensions produce impoverished retirees with greatly limited purchasing power and this, sooner rather than later, will end up affecting consumption and economic activity. It would seem that talking about 2030 or 2040 is referring to the future. However, in terms of savings or retirement, this is tomorrow or, at most, “next week”, because any retirement planning needs time in order to become fully effective. No fewer than 18-20 years are needed to generate a complementary pension that proves sufficient to offset the reduction in the public pensions. This means that if, say, tomorrow morning workers began to save for their own pension in a way similar to the British model, linked to their work, everyone would receive a pension supplement from that very moment, as one euro saved is worth twice as much as not having savings. But the benefit will be for those who are now under 45 years of age, because, when they retire, they will have been saving for their pension for at least 20 years. They will thus have sufficient resources to complement the public pensions, precisely when it is estimated that these will be suffering from the lowest replacement rates ever.

Faced with a reality such as aging, the worst prescription is to do nothing. If action is not taken with foresight, far in advance, we could find ourselves in a situation where 30 percent of citizens are not only retired and, logically, do not work, but will also have very low purchasing power and then, who will drive economic demand and consumption?

TO SPEAK OF PENSIONS IS TO SPEAK OF INSURANCE

While there are several financial agents offering pensions-related savings products, the fact is that the true specialists in managing the uncertain future are the insurance companies.

First of all, they are the sole experts in medium and long-term investments. Managing one customer’s risks for one or two years is not the same as doing so for a period of thirty or more years. The latter calls for a degree of specialization and financial capabilities for the management of such risks that can solely be provided by life insurance companies.

In addition, insurance also assumes the risk of longevity, that is to say, when a company undertakes to pay a customer a life annuity, it will do so until the end, regardless of whether that person ends up living more years than were estimated for their population cohort. This makes insurance products the best option when seeking to complement the revenue from public pensions.

In short, insurance companies, especially the most solvent ones, are the most reliable partner, not only when it comes to talking about the future, but also preparing the future for each and every one of us.